FINANCE

Surrey’s Premier Lifestyle Magazine

An Unjust Bounty

Simon Lewis, CEO at Partridge Muir & Warren sheds light on a new ‘stealth tax’ targeted primarily at the wealthy when they die.

Government must have realised that with the anticipated post-Brexit reduction in the number of people (potential tax payers) entering the country, it will need to make sure that it collects more tax from the dead ones 'departing' if it is to balance the books.

Particularly so since Philip Hammond, Chancellor of the Exchequer, discovered that increasing tax rates is not popular and was forced to make a U-turn on his plan to increase National Insurance for the self-employed to show respect for an ill-advised manifesto pledge. In the circumstances, creative thinking is required and what better way for politicians to be creative than to find fees that are charged by the Government and conjure up justifications to dramatically increase them. The scheduled increase in probate fees is a very good example of this trend.

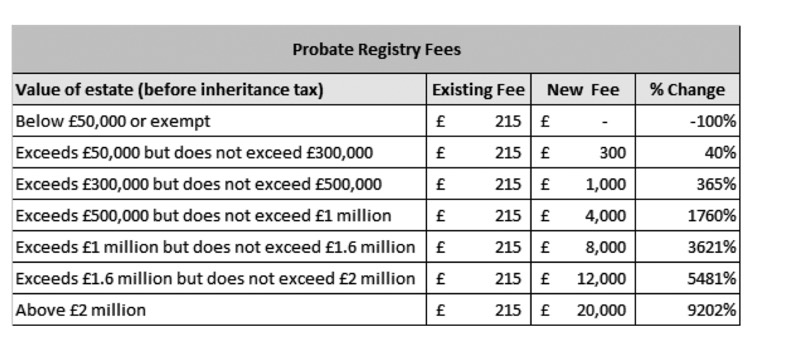

An increase in probate fees was proposed in February last year and was followed by a brief consultation period. The overwhelming response to the consultation opposed the change but, unsurprisingly, the proposals will nevertheless be taking effect from the middle of May. For some estates, the probate fee charged will increase from £215 to £20,000. The justification found on the government’s website is as follows: “Court fees are never popular but they are necessary if we are, as a nation, to live within our means. These proposals would raise around an additional £250 million a year, which is a critical contribution to cutting the deficit and reducing the burden on the taxpayer of running the courts and tribunals.”

It sounds a compelling argument but a more realistic explanation might have been “Rather than rely on all taxpayers to bear their share of the cost of running an essential public service, we have decided that our popularity will be less affected if we load much of the burden on the few”.

The current position is that where a deceased person’s estate exceeds £5,000, a Grant of Probate is required before the estate can be dealt with. To obtain a Grant of Probate (or Letter of Administration where there is not a valid will) an application must be made to the Probate Registry. There is currently a flat fee of £215 (reduced to £155 if submitted by a solicitor) to reflect the fact that the work required by the Registry is broadly the same whatever the value recorded. According to the Government’s own figures the existing fee raises £45 million per annum, which is broadly sufficient to cover the associated administration costs.

A new banded tariff will replace the current fixed fee, harvesting up to 1% of the estate.

The actual date of death is immaterial; it is the date of the application for a grant that will govern whether the new fees apply, which explains why the Probate Registry has geared up for a marked influx in applications ahead of this change.

Particularly so since Philip Hammond, Chancellor of the Exchequer, discovered that increasing tax rates is not popular and was forced to make a U-turn on his plan to increase National Insurance for the self-employed to show respect for an ill-advised manifesto pledge. In the circumstances, creative thinking is required and what better way for politicians to be creative than to find fees that are charged by the Government and conjure up justifications to dramatically increase them. The scheduled increase in probate fees is a very good example of this trend.

An increase in probate fees was proposed in February last year and was followed by a brief consultation period. The overwhelming response to the consultation opposed the change but, unsurprisingly, the proposals will nevertheless be taking effect from the middle of May. For some estates, the probate fee charged will increase from £215 to £20,000. The justification found on the government’s website is as follows: “Court fees are never popular but they are necessary if we are, as a nation, to live within our means. These proposals would raise around an additional £250 million a year, which is a critical contribution to cutting the deficit and reducing the burden on the taxpayer of running the courts and tribunals.”

It sounds a compelling argument but a more realistic explanation might have been “Rather than rely on all taxpayers to bear their share of the cost of running an essential public service, we have decided that our popularity will be less affected if we load much of the burden on the few”.

The current position is that where a deceased person’s estate exceeds £5,000, a Grant of Probate is required before the estate can be dealt with. To obtain a Grant of Probate (or Letter of Administration where there is not a valid will) an application must be made to the Probate Registry. There is currently a flat fee of £215 (reduced to £155 if submitted by a solicitor) to reflect the fact that the work required by the Registry is broadly the same whatever the value recorded. According to the Government’s own figures the existing fee raises £45 million per annum, which is broadly sufficient to cover the associated administration costs.

A new banded tariff will replace the current fixed fee, harvesting up to 1% of the estate.

The actual date of death is immaterial; it is the date of the application for a grant that will govern whether the new fees apply, which explains why the Probate Registry has geared up for a marked influx in applications ahead of this change.

The Government is making much of the fact that a substantially increased lower threshold will mean that fewer estates will be required to pay a fee. It estimates that 58% of all estates will effectively be exempt. This is good news. However, the ‘giveaway’ is only costing around £25 million per annum when based on the current fee scale, which compares unfavourably to the additional £275 million it will be taking from the remaining 42% of estates.

Executors of estates that have not already applied for probate must do so without delay if they do not want to be caught by the fee increases. For those that need to submit an IHT400 account to HMRC (estates in excess of £1 million, or in excess of the £325,000 nil rate band if no Inheritance Tax exemption or transferable nil rate band is being claimed) it is usually necessary to wait for HMRC to return a stamped IHT421 to confirm all IHT due has been paid before applying for the grant; although a special dispensation to circumvent this has been recently announced.

It is important to appreciate that this new ‘tax’ is not deductible when calculating the amount of IHT payable. Estates might therefore pay tax on a tax. In other words, beneficiaries would lose up to £20,000 paid as a probate fee, plus a further £8,000 (40% of £20,000) IHT on an amount that they will not inherit because it has already been paid away.

These fee changes may encourage married couples to consider owning assets jointly. When the first death occurs, assets pass automatically to the surviving spouse by survivorship with the result that no grant is needed and therefore no probate fee incurred. However, this might create conflict with existing tax planning arrangements or change the intended hierarchy of control over assets.

From a planning perspective, the aim should be to minimise your estate on death when you believe that the value is likely to be close to one of the fee band thresholds (see table). This would be particularly effective for those with an estate valued at just over £2 million because this figure is also the current threshold for the abatement (more tax!) of the residence nil rate band (RNRB) that came into effect on 6 April.

Estate values can be minimised by putting money into trust. It is worth checking that any life policies you might own are held in this way. The trust would not necessarily need to be effective for IHT purposes; the objective is to reduce the value of what you own at the point of death.

In fact, ‘deathbed’ gifting is likely to be an effective option for many, although it is clearly not the ideal time to be thinking about tax planning. For those facing an IHT bill, gifts to charity immediately prior to death (i.e. not just relying on bequests in your will) might be particularly effective. For example, giving away £1,000 to a charity from your deathbed when your estate is worth £2,001,000 will have the effect of saving your beneficiaries £8,000 in probate fees plus (assuming you qualify for the RNRB) a further saving in IHT of £600. This latter figure is made up of the 40% IHT charge (£400) plus a further 40% on the portion of the RNRB recovered (yes, it is complicated!). So, in summary, a charitable gift of £1,000 would save this estate’s beneficiaries £8,600 in ‘tax’, giving a net gain of £7,600.

There is another matter to consider.

A Grant of Probate is required before estate assets can be accessed. This means that executors or beneficiaries might be required to look to their own resources to finance a probate fee of up to £20,000. As the Government’s guidance notes point out, “All fees are payable in advance of the service being provided. The sanction for non-payment is that the service will not be provided.”

Estate planning has become even more complicated. We would be happy to help you understand your options.

Executors of estates that have not already applied for probate must do so without delay if they do not want to be caught by the fee increases. For those that need to submit an IHT400 account to HMRC (estates in excess of £1 million, or in excess of the £325,000 nil rate band if no Inheritance Tax exemption or transferable nil rate band is being claimed) it is usually necessary to wait for HMRC to return a stamped IHT421 to confirm all IHT due has been paid before applying for the grant; although a special dispensation to circumvent this has been recently announced.

It is important to appreciate that this new ‘tax’ is not deductible when calculating the amount of IHT payable. Estates might therefore pay tax on a tax. In other words, beneficiaries would lose up to £20,000 paid as a probate fee, plus a further £8,000 (40% of £20,000) IHT on an amount that they will not inherit because it has already been paid away.

These fee changes may encourage married couples to consider owning assets jointly. When the first death occurs, assets pass automatically to the surviving spouse by survivorship with the result that no grant is needed and therefore no probate fee incurred. However, this might create conflict with existing tax planning arrangements or change the intended hierarchy of control over assets.

From a planning perspective, the aim should be to minimise your estate on death when you believe that the value is likely to be close to one of the fee band thresholds (see table). This would be particularly effective for those with an estate valued at just over £2 million because this figure is also the current threshold for the abatement (more tax!) of the residence nil rate band (RNRB) that came into effect on 6 April.

Estate values can be minimised by putting money into trust. It is worth checking that any life policies you might own are held in this way. The trust would not necessarily need to be effective for IHT purposes; the objective is to reduce the value of what you own at the point of death.

In fact, ‘deathbed’ gifting is likely to be an effective option for many, although it is clearly not the ideal time to be thinking about tax planning. For those facing an IHT bill, gifts to charity immediately prior to death (i.e. not just relying on bequests in your will) might be particularly effective. For example, giving away £1,000 to a charity from your deathbed when your estate is worth £2,001,000 will have the effect of saving your beneficiaries £8,000 in probate fees plus (assuming you qualify for the RNRB) a further saving in IHT of £600. This latter figure is made up of the 40% IHT charge (£400) plus a further 40% on the portion of the RNRB recovered (yes, it is complicated!). So, in summary, a charitable gift of £1,000 would save this estate’s beneficiaries £8,600 in ‘tax’, giving a net gain of £7,600.

There is another matter to consider.

A Grant of Probate is required before estate assets can be accessed. This means that executors or beneficiaries might be required to look to their own resources to finance a probate fee of up to £20,000. As the Government’s guidance notes point out, “All fees are payable in advance of the service being provided. The sanction for non-payment is that the service will not be provided.”

Estate planning has become even more complicated. We would be happy to help you understand your options.

essence info

Simon Lewis is writing on behalf of Partridge Muir & Warren Ltd (PMW), Chartered Financial Planners, based in Esher. The Company has specialised in providing wealth management solutions to private clients for 46 years. Simon is an independent financial adviser, chartered financial planner and chartered fellow of the Chartered Institute for Securities and Investment. The opinions outlined in this article are those of the writer and should not be construed as individual advice. To find out more about financial advice and investment options please contact Simon at Partridge Muir & Warren Ltd. Partridge Muir & Warren Ltd is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority.Telephone: 01372 471 550

Email: simon.lewis@pmw.co.uk

Website: www.pmw.co.uk

"For some estates, the probate fee charged

will increase from £215 to £20,000."