INTERVIEW

Surrey’s Premier Lifestyle Magazine

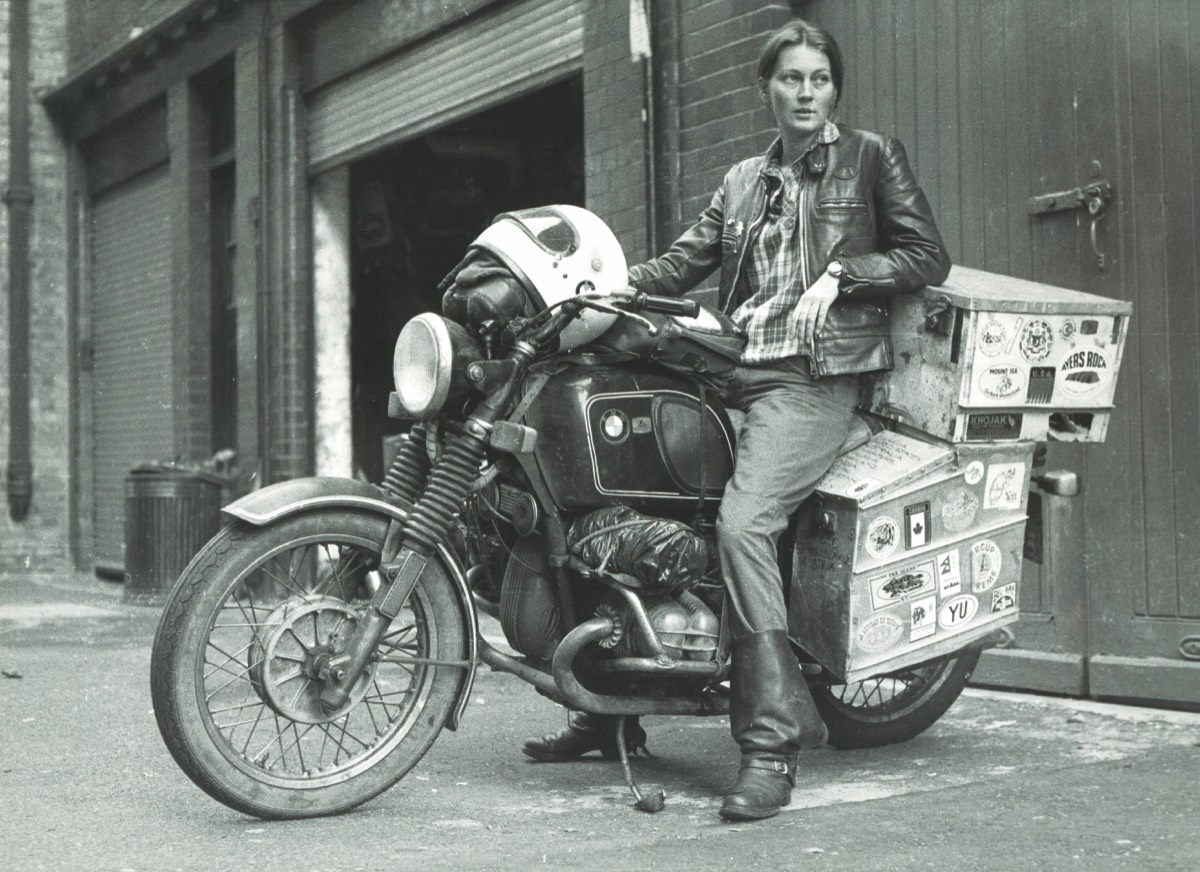

Lone rider

In 1982, at twenty-three and halfway through her architecture studies, Elspeth Beard left her family and friends in London and set off on a 35,000-mile solo adventure around the world on her 1974 BMW R60/6. When she returned to London nearly two and a half years later she was stones lighter and decades wiser. She finally got round to chronicling her adventures and has recently published a book about them. Andrew Peters talked to her about her once in a lifetime experience.

First bike, a Yamaha YB100, parked outside Elspeth's home in central London 1979 - All images photo copyright Elspeth Beard unless stated.

Q Elspeth, can you pinpoint the time when the idea to ride a motorbike solo around the world first came into your head?

A I got my first bike when I was seventeen; it was a 100cc Yamaha and I saw it simply as a cheap and efficient way of getting around London, but it did have its limitations. So, a year later, I upgraded to a Honda 250cc and that was when I started to realise the travelling potential of a bike. I soon got bored with the Honda and in 1979 I bought a second hand BMW R60/6. It was a 1974 model, with about 30,000 miles on the clock. My choice of bike was more luck than judgement as my boyfriend at the time knew someone who wanted to sell his bike.

With my BMW I felt I could go anywhere. It gave me an immense sense of freedom and over the next couple of years I gradually travelled further afield, starting with a tour of Scotland, then Ireland, and progressing to a two month trip around Europe in the summer of 1980. The following summer I persuaded my brother to meet me in Los Angeles where we bought an old BMW R75/5 and rode together across to Detroit. All these trips gradually built up my confidence, not only about travelling (much of it alone) but also how to look after myself and my bike. I started to dream of riding around the world, but never really thought it would become a reality.

Q You decided on two wheels rather than four, where did your passion for bikes come from?

A No one in my family rode bikes and I got little encouragement from my parents as they were both doctors and had seen many injuries as a result of motorbike accidents. However, many of my friends had bikes and I needed transport to get around London. In those days you could ride a bike on a provisional licence without taking any kind of test. So my mates taught me to ride and I progressed from there.

Q How much did you pay for the BMW R60/6 bike at the time?

A I bought my bike in 1979 for £900.

Q What was the reaction of your parents and friends when you told them what you were proposing to do?

A My parents showed little or no interest in my trip. Having worked in Accident & Emergency, my mother hated motorbikes and did her utmost to stop me: she even threatened to disinherit me! But my parents’ resistance only made me more determined.

In fairness to my mother, she couldn’t really understand anything that was unconventional and her apparent lack of interest was probably her way of dealing with my trip. Like any good mother, she worried about her children and in her view my life had taken a wrong turn. As for my father, he was entirely in his own world.

Q What were the scariest, funniest and happiest moments?

A The scariest time was travelling towards the Iranian border through Baluchistan in western Pakistan. The Russians had invaded Afghanistan to the north so there were a lot of refugees wandering in the desert openly carrying rifles and knives. The road was almost nonexistent so riding the bike was challenging.

The happiest time was undoubtedly meeting and falling in love with Robert. Having travelled on my own for over a year and a half, it changed everything. I had not seen a fellow long distance motorcycle traveller, and neither had Robert, so it was a rare sight in those days.

We bumped into each other riding our bikes through the streets of Kathmandu. Catching sight of each other, we both stopped dead, jumped off our bikes and then sat on the side of the road and talked nonstop for over three hours. Robert was Dutch and had emigrated to Australia a couple of years earlier, but he hadn’t been able to settle so had decided to ride his bike back to Holland. Travelling with Robert changed my trip from day to day survival to something that almost started to feel like a holiday. The risks when travelling alone are far greater and mentally you have to be very strong. I had become weary of always having to sort out and deal with problems entirely on my own. Whether it was problems with my bike or being ill or simply trying to find the right road, just having someone to share and discuss things with made all the difference – it no longer felt like an endurance test.

A I got my first bike when I was seventeen; it was a 100cc Yamaha and I saw it simply as a cheap and efficient way of getting around London, but it did have its limitations. So, a year later, I upgraded to a Honda 250cc and that was when I started to realise the travelling potential of a bike. I soon got bored with the Honda and in 1979 I bought a second hand BMW R60/6. It was a 1974 model, with about 30,000 miles on the clock. My choice of bike was more luck than judgement as my boyfriend at the time knew someone who wanted to sell his bike.

With my BMW I felt I could go anywhere. It gave me an immense sense of freedom and over the next couple of years I gradually travelled further afield, starting with a tour of Scotland, then Ireland, and progressing to a two month trip around Europe in the summer of 1980. The following summer I persuaded my brother to meet me in Los Angeles where we bought an old BMW R75/5 and rode together across to Detroit. All these trips gradually built up my confidence, not only about travelling (much of it alone) but also how to look after myself and my bike. I started to dream of riding around the world, but never really thought it would become a reality.

Q You decided on two wheels rather than four, where did your passion for bikes come from?

A No one in my family rode bikes and I got little encouragement from my parents as they were both doctors and had seen many injuries as a result of motorbike accidents. However, many of my friends had bikes and I needed transport to get around London. In those days you could ride a bike on a provisional licence without taking any kind of test. So my mates taught me to ride and I progressed from there.

Q How much did you pay for the BMW R60/6 bike at the time?

A I bought my bike in 1979 for £900.

Q What was the reaction of your parents and friends when you told them what you were proposing to do?

A My parents showed little or no interest in my trip. Having worked in Accident & Emergency, my mother hated motorbikes and did her utmost to stop me: she even threatened to disinherit me! But my parents’ resistance only made me more determined.

In fairness to my mother, she couldn’t really understand anything that was unconventional and her apparent lack of interest was probably her way of dealing with my trip. Like any good mother, she worried about her children and in her view my life had taken a wrong turn. As for my father, he was entirely in his own world.

Q What were the scariest, funniest and happiest moments?

A The scariest time was travelling towards the Iranian border through Baluchistan in western Pakistan. The Russians had invaded Afghanistan to the north so there were a lot of refugees wandering in the desert openly carrying rifles and knives. The road was almost nonexistent so riding the bike was challenging.

The happiest time was undoubtedly meeting and falling in love with Robert. Having travelled on my own for over a year and a half, it changed everything. I had not seen a fellow long distance motorcycle traveller, and neither had Robert, so it was a rare sight in those days.

We bumped into each other riding our bikes through the streets of Kathmandu. Catching sight of each other, we both stopped dead, jumped off our bikes and then sat on the side of the road and talked nonstop for over three hours. Robert was Dutch and had emigrated to Australia a couple of years earlier, but he hadn’t been able to settle so had decided to ride his bike back to Holland. Travelling with Robert changed my trip from day to day survival to something that almost started to feel like a holiday. The risks when travelling alone are far greater and mentally you have to be very strong. I had become weary of always having to sort out and deal with problems entirely on my own. Whether it was problems with my bike or being ill or simply trying to find the right road, just having someone to share and discuss things with made all the difference – it no longer felt like an endurance test.

Mark Twain House and Museum, Hartford PHOto Copyright: Wasin Pummarin | www.123rf.com

The '90-Mile Straight' on the Eyre Highway in Western Australia, one of the longest straight stretches of road in the world

Outside Elspeth's parents' garage in central London in 1984, after 35,000 miles and over two years on the road

Q How did that experience change your life?

A For me I think it was the fact I had succeeded and survived against all the odds, I came back a changed person, I was not afraid of anything. I learnt so much about myself as I had been tested to my limits, and this gives a sort of inner strength and confidence to tackle anything the world can throw at you. I would never take no for an answer (and still don’t!). If I couldn’t achieve something in one way I would go around it and tackle the problem from another direction. I learnt to think outside the box and be imaginative and resourceful, qualities I have applied to my life and work ever since.

Q Knowing what you know, would you have done that trip?

A Absolutely, without a doubt. It’s important to take yourself out

of your comfort zone so you can learn about yourself.

Q What sort of things went through your mind when you were travelling long distances in a day?

A Travelling across America at the beginning of the journey my thoughts were often of my boyfriend who had broken my heart just before I left. By the time I had ridden across Australia, I had put my demons to rest; crossing the continent had been so tough my mind had been occupied with just surviving.

Much of the time I would be thinking about my bike and working out petrol consumption, when I would next have to fill up, my oil consumption and when I would next have to service her. I would think about my route and plan how far I would try and get the following day. I would calculate how much money I had left and work out how much I was spending a day. The fact that my funds were so limited was a constant worry, not knowing what lay ahead or what expenditures I would have, as the only fixed cost I had was fuel.

Q Did you ever want to stop and turn back?

A Turning back was never really an option; by the time I had reached Australia and I was on the other side of the world it was just as easy to carry on. After I had been on the road for nearly two years I was feeling very tired and weary and I did just want to get home. But in those days custom officials would write your bike details into your passport making it impossible to exit the country without your bike, so leaving the bike and flying home was not an option. The only choice I had was to ride all the way back home.

Q How did you feel at the end of it all? Did you want to do it again?

A I returned home at the end of 1984 and found readjusting extremely difficult. It was not easy to return after such an adventure when living life on the open road had been so intense. I had lived every minute of every day for over two years. No one wanted to know about my journey as they couldn’t relate to it or understand what I had experienced. This made me feel very lonely and isolated.

I have never stopped travelling and went around the world again in 2003. I have biked in South America and Africa, as well as numerous trips across the States. But I don’t feel the need to repeat the trip as there are so many other places in the world still left to see. It’s important to remember that although you can say you have travelled around the world, all you have actually seen is both sides of a single line on your map.

Q Have you ever been back to the places you saw?

A I have generally tried to avoid going back as this is never a good idea in my view. When I went back to Sydney in 2003 I was shocked at how the place had changed, which was probably partly due to the Olympics. It had gone from a relatively small provincial city full of character: in 1983 it was off the beaten track and felt as if you were on the edge of civilisation in some remote outpost. In 2003 the city and its skyline had been transformed: it was all glitzy and shiny with huge, ugly new buildings and a lot of the old characterful areas had been demolished. I believe old buildings are an important part of a country’s heritage and it seemed this had been lost in the rush.

In 1998 I went back to Kathmandu where I picked up a Royal Enfield motorbike and rode it to Lhasa in Tibet. When I had visited the capital before, in 1983, it was a ‘cool’ travellers’ retreat, a quiet and peaceful place full of unusual, slightly quirky travellers and serious mountaineers preparing to climb Everest. Fifteen years later it was full of backpackers with every sort of adventure advertised from river rafting, bungee jumping, motorbike and elephant rides etc. The list of ‘adventures’ offered was astounding and, of course, fully guided treks to absolutely anywhere. Sometimes I think it’s best to remember places as they were.

Q Patrick Leigh Fermor’s book ‘A Time of Gifts’ captures a fast disappearing world just before the advent of WWII. Do you think you experienced a world that has now passed into the history books?

A Travelling is certainly very different nowadays and I’m very glad I saw and travelled the world when I did. The biggest change is the information available now and the fact you can find out about anything and everything, anywhere, all at your fingertips via a smart phone. This has transformed the way people travel because it takes away the fear of the unknown and provides a degree of ‘comfort’ which encourages many more people to take to the road. Although this is a good thing, I do think something has been lost. Knowing what’s around the next corner and being able to plan everything to the last detail takes away uncertainty and ultimately the adventure. The journey for me was not about sitting on my bike for four to five hours a day, it was about the experiences; the people encountered, the breakdowns, the accidents, getting lost and the bizarre situations you find yourself in when the unexpected happens. With so much technology and information available these experiences are minimised and there’s a danger the journey is no longer an adventure but simply a series of days riding a bike.

I recall many times when I was lost and had to ask one of the locals the way; I would then often be invited to join them for tea, then dinner, then asked to stay with the family for the night. It’s those experiences that are ‘the journey’ and don’t happen when you are following a red line on your GPS.

A For me I think it was the fact I had succeeded and survived against all the odds, I came back a changed person, I was not afraid of anything. I learnt so much about myself as I had been tested to my limits, and this gives a sort of inner strength and confidence to tackle anything the world can throw at you. I would never take no for an answer (and still don’t!). If I couldn’t achieve something in one way I would go around it and tackle the problem from another direction. I learnt to think outside the box and be imaginative and resourceful, qualities I have applied to my life and work ever since.

Q Knowing what you know, would you have done that trip?

A Absolutely, without a doubt. It’s important to take yourself out

of your comfort zone so you can learn about yourself.

Q What sort of things went through your mind when you were travelling long distances in a day?

A Travelling across America at the beginning of the journey my thoughts were often of my boyfriend who had broken my heart just before I left. By the time I had ridden across Australia, I had put my demons to rest; crossing the continent had been so tough my mind had been occupied with just surviving.

Much of the time I would be thinking about my bike and working out petrol consumption, when I would next have to fill up, my oil consumption and when I would next have to service her. I would think about my route and plan how far I would try and get the following day. I would calculate how much money I had left and work out how much I was spending a day. The fact that my funds were so limited was a constant worry, not knowing what lay ahead or what expenditures I would have, as the only fixed cost I had was fuel.

Q Did you ever want to stop and turn back?

A Turning back was never really an option; by the time I had reached Australia and I was on the other side of the world it was just as easy to carry on. After I had been on the road for nearly two years I was feeling very tired and weary and I did just want to get home. But in those days custom officials would write your bike details into your passport making it impossible to exit the country without your bike, so leaving the bike and flying home was not an option. The only choice I had was to ride all the way back home.

Q How did you feel at the end of it all? Did you want to do it again?

A I returned home at the end of 1984 and found readjusting extremely difficult. It was not easy to return after such an adventure when living life on the open road had been so intense. I had lived every minute of every day for over two years. No one wanted to know about my journey as they couldn’t relate to it or understand what I had experienced. This made me feel very lonely and isolated.

I have never stopped travelling and went around the world again in 2003. I have biked in South America and Africa, as well as numerous trips across the States. But I don’t feel the need to repeat the trip as there are so many other places in the world still left to see. It’s important to remember that although you can say you have travelled around the world, all you have actually seen is both sides of a single line on your map.

Q Have you ever been back to the places you saw?

A I have generally tried to avoid going back as this is never a good idea in my view. When I went back to Sydney in 2003 I was shocked at how the place had changed, which was probably partly due to the Olympics. It had gone from a relatively small provincial city full of character: in 1983 it was off the beaten track and felt as if you were on the edge of civilisation in some remote outpost. In 2003 the city and its skyline had been transformed: it was all glitzy and shiny with huge, ugly new buildings and a lot of the old characterful areas had been demolished. I believe old buildings are an important part of a country’s heritage and it seemed this had been lost in the rush.

In 1998 I went back to Kathmandu where I picked up a Royal Enfield motorbike and rode it to Lhasa in Tibet. When I had visited the capital before, in 1983, it was a ‘cool’ travellers’ retreat, a quiet and peaceful place full of unusual, slightly quirky travellers and serious mountaineers preparing to climb Everest. Fifteen years later it was full of backpackers with every sort of adventure advertised from river rafting, bungee jumping, motorbike and elephant rides etc. The list of ‘adventures’ offered was astounding and, of course, fully guided treks to absolutely anywhere. Sometimes I think it’s best to remember places as they were.

Q Patrick Leigh Fermor’s book ‘A Time of Gifts’ captures a fast disappearing world just before the advent of WWII. Do you think you experienced a world that has now passed into the history books?

A Travelling is certainly very different nowadays and I’m very glad I saw and travelled the world when I did. The biggest change is the information available now and the fact you can find out about anything and everything, anywhere, all at your fingertips via a smart phone. This has transformed the way people travel because it takes away the fear of the unknown and provides a degree of ‘comfort’ which encourages many more people to take to the road. Although this is a good thing, I do think something has been lost. Knowing what’s around the next corner and being able to plan everything to the last detail takes away uncertainty and ultimately the adventure. The journey for me was not about sitting on my bike for four to five hours a day, it was about the experiences; the people encountered, the breakdowns, the accidents, getting lost and the bizarre situations you find yourself in when the unexpected happens. With so much technology and information available these experiences are minimised and there’s a danger the journey is no longer an adventure but simply a series of days riding a bike.

I recall many times when I was lost and had to ask one of the locals the way; I would then often be invited to join them for tea, then dinner, then asked to stay with the family for the night. It’s those experiences that are ‘the journey’ and don’t happen when you are following a red line on your GPS.

The Golden Triangle: the northern-most point of Thailand

Q Do you think we have lost a sense of the unknown and adventure in the digital internet age?

A Yes, without doubt.

Q What was the best and worst reaction to people seeing a woman riding a bike?

A I found some parts of America were fairly anti biker, but their attitudes changed completely when I removed my helmet and they saw I was a woman. In less developed countries they seemed puzzled and even slightly bemused seeing a woman riding a big bike.

Q Do you think attitudes towards women have changed at all or are they just kept hidden away?

A I think attitudes towards women riding motorbikes have changed and you see far more women on bikes these days. I would like to think the biking industry has woken up and become more accepting and welcoming to women, however the reality may simply be they saw the potential of a previously untapped market!

In general I think attitudes have changed towards women, but we still have a long way to go to achieve true equality. I think it’s important that women get out there and do things to prove we are just as capable and don’t just talk about it. Changes in the law have helped, but this doesn’t deal with deep-rooted prejudices: respect is not given, we have to earn it.

Q You’re an architect and converted a disused water tower into a home. What do you deem the greater challenge: the circumnavigation or the renovation?

A In October 1988 I found a 130 foot high derelict Victorian water tower for sale. The moment I saw the tower I knew I had to have it and I bought it without a moment’s hesitation. Two years after buying the tower, I became a mother, lost my father to a heart attack and was forced to move out of my childhood home and live in the tower which was still a building site with a six month old baby; I also became a single mum.

This was the toughest time in my life, harder than anything I had encountered on my trip, in part because I had always known my trip would be a solo venture, whereas I had taken on my child and the tower on the understanding they were shared endeavours. Sadly I was wrong and I had to deal with everything on my own.

Q Your architecture practice focuses on more unusual projects. What are you working on now?

A I’m working on several barn conversions, a Grade I listed almshouse, a new build house in London and about twenty other smaller projects.

Q You have lived and worked in England, but did you ever contemplate living elsewhere after your travels?

A No. England is my home.

Q You are a free spirit: have you any further travel plans?

A I have never stopped travelling and am planning a motorbike trip in Pakistan in September.

A Yes, without doubt.

Q What was the best and worst reaction to people seeing a woman riding a bike?

A I found some parts of America were fairly anti biker, but their attitudes changed completely when I removed my helmet and they saw I was a woman. In less developed countries they seemed puzzled and even slightly bemused seeing a woman riding a big bike.

Q Do you think attitudes towards women have changed at all or are they just kept hidden away?

A I think attitudes towards women riding motorbikes have changed and you see far more women on bikes these days. I would like to think the biking industry has woken up and become more accepting and welcoming to women, however the reality may simply be they saw the potential of a previously untapped market!

In general I think attitudes have changed towards women, but we still have a long way to go to achieve true equality. I think it’s important that women get out there and do things to prove we are just as capable and don’t just talk about it. Changes in the law have helped, but this doesn’t deal with deep-rooted prejudices: respect is not given, we have to earn it.

Q You’re an architect and converted a disused water tower into a home. What do you deem the greater challenge: the circumnavigation or the renovation?

A In October 1988 I found a 130 foot high derelict Victorian water tower for sale. The moment I saw the tower I knew I had to have it and I bought it without a moment’s hesitation. Two years after buying the tower, I became a mother, lost my father to a heart attack and was forced to move out of my childhood home and live in the tower which was still a building site with a six month old baby; I also became a single mum.

This was the toughest time in my life, harder than anything I had encountered on my trip, in part because I had always known my trip would be a solo venture, whereas I had taken on my child and the tower on the understanding they were shared endeavours. Sadly I was wrong and I had to deal with everything on my own.

Q Your architecture practice focuses on more unusual projects. What are you working on now?

A I’m working on several barn conversions, a Grade I listed almshouse, a new build house in London and about twenty other smaller projects.

Q You have lived and worked in England, but did you ever contemplate living elsewhere after your travels?

A No. England is my home.

Q You are a free spirit: have you any further travel plans?

A I have never stopped travelling and am planning a motorbike trip in Pakistan in September.

essence info

Lone Rider by Elspeth Beard is published by Michael O’Mara Books, priced at £14.99Website: www.mombooks.com

“Changes in the law have helped, but this doesn’t deal with deep-rooted prejudices (against women): respect is not given, we have to earn it.”

Elspeth Beard