HAUTE COUTURE

Surrey’s Premier Lifestyle Magazine

King of couture

A new exhibition at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion, showcases the work and legacy of the innovative Spanish couturier Cristóbal Balenciaga.

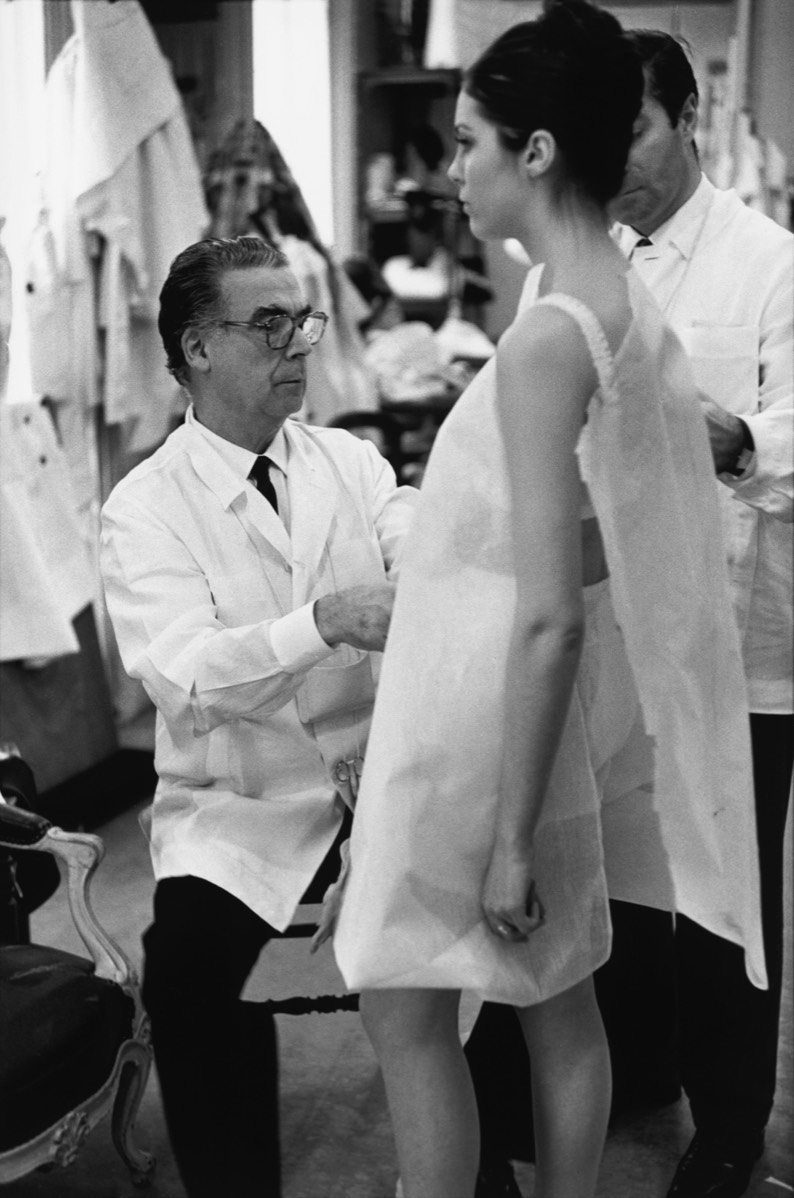

Cristóbal Balenciaga at work, 1968, Paris, France. Photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson. © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Known as ‘The Master’ of haute couture, Cristóbal Balenciaga was one of the most innovative and influential fashion designers of the last century. His exquisite craftsmanship and pioneering use of fabrics revolutionised the female silhouette, setting the tone for modern fashion.

Balenciaga’s impact on fashion has been profound. Yet to many of us he remains an unknown, an enigma, something he inadvertedly helped create as throughout his life he shunned publicity and gave only one interview during his 50-year career.

Now a new exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum: Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion marks the centenary of the opening of Balenciaga’s first fashion house in San Sebastian, Spain, and the 80th anniversary of the opening of his famous fashion house in Paris. The V&A houses the largest collection of Balenciaga in the UK, initiated in the 1970s by photographer Cecil Beaton, Balenciaga’s longstanding friend.

Balenciaga is not associated with a signature outfit, as Coco Chanel, to name but one, nor with a pivotal moment, as with Christian Dior and the New Look of 1947, nor a cultural phenomenon like Vivienne Westwood and punk. From the moment he opened his Paris house, Balenciaga’s clothes struck a note of simplicity that at times had a regal presence, at others a graphic grace. But, as with Chanel, Balenciaga believed clothes should not hamper the body. His clothes became easier to engage with until, by the mid-1950s, many could be slipped on and off over the head. He reshaped women’s silhouettes in the 1950s. In the 1960s the purity of his masterpieces lifted his work into the arena of art. His cut was legendary. Nothing fitted the body with the supple ease of a Balenciaga suit, and once women had worn his clothes they were often unwilling to wear anything else.

Born in 1895 in Getaria, a small fishing village in the Basque region of northern Spain, Cristóbal Balenciaga was introduced to fashion by his mother, a seamstress. Her clients included the most fashionable and glamorous women in the village. Aged just twelve, he began an apprenticeship at a tailor’s in the neighbouring fashionable resort of San Sebastian, where in 1917 he established his first fashion house, named Eisa – a shortening of his mother’s maiden name.

Balenciaga opened fashion houses in Barcelona and Madrid before moving to Paris in 1937. The house on Avenue Georges V quickly became the city’s most expensive and exclusive couturier. His early training set him apart from other couturiers of the time: he knew his craft inside out and was adept at every stage of the making process, from pattern drafting to cutting, assembling and finishing a garment. For him, the design process started with the fabric rather than with a sketch. “It’s the fabric that decides,” he stated, proving he knew how to exploit materials to the very best effect.

Balenciaga’s impact on fashion has been profound. Yet to many of us he remains an unknown, an enigma, something he inadvertedly helped create as throughout his life he shunned publicity and gave only one interview during his 50-year career.

Now a new exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum: Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion marks the centenary of the opening of Balenciaga’s first fashion house in San Sebastian, Spain, and the 80th anniversary of the opening of his famous fashion house in Paris. The V&A houses the largest collection of Balenciaga in the UK, initiated in the 1970s by photographer Cecil Beaton, Balenciaga’s longstanding friend.

Balenciaga is not associated with a signature outfit, as Coco Chanel, to name but one, nor with a pivotal moment, as with Christian Dior and the New Look of 1947, nor a cultural phenomenon like Vivienne Westwood and punk. From the moment he opened his Paris house, Balenciaga’s clothes struck a note of simplicity that at times had a regal presence, at others a graphic grace. But, as with Chanel, Balenciaga believed clothes should not hamper the body. His clothes became easier to engage with until, by the mid-1950s, many could be slipped on and off over the head. He reshaped women’s silhouettes in the 1950s. In the 1960s the purity of his masterpieces lifted his work into the arena of art. His cut was legendary. Nothing fitted the body with the supple ease of a Balenciaga suit, and once women had worn his clothes they were often unwilling to wear anything else.

Born in 1895 in Getaria, a small fishing village in the Basque region of northern Spain, Cristóbal Balenciaga was introduced to fashion by his mother, a seamstress. Her clients included the most fashionable and glamorous women in the village. Aged just twelve, he began an apprenticeship at a tailor’s in the neighbouring fashionable resort of San Sebastian, where in 1917 he established his first fashion house, named Eisa – a shortening of his mother’s maiden name.

Balenciaga opened fashion houses in Barcelona and Madrid before moving to Paris in 1937. The house on Avenue Georges V quickly became the city’s most expensive and exclusive couturier. His early training set him apart from other couturiers of the time: he knew his craft inside out and was adept at every stage of the making process, from pattern drafting to cutting, assembling and finishing a garment. For him, the design process started with the fabric rather than with a sketch. “It’s the fabric that decides,” he stated, proving he knew how to exploit materials to the very best effect.

LOADING

Dovima with Sacha, cloche and suit by Balenciaga, Café des Deux Magots, Paris, 1955. Photograph by Richard Avedon © The Richard Avedon Foundation

Balenciaga’s Spanish heritage influenced many of his most iconic designs. His wide-hipped ‘Infanta’ dresses from the late 1930s drew on the portraiture of the seventeenth century Spanish artist Diego Velázquez. Flamenco dresses, matador outfits and black lace – seen in the traditional mantilla shawls worn by women at special ceremonies and during Spanish Holy Week – were also frequent motifs.

In the 1950s, the later phase of his career, Balenciaga pioneered new shapes never before seen in women’s fashion. These radical designs evolved gradually as he refined and reworked the same ideas from season to season. Volume filled the ‘balloon hems’ of his early 1950s’ dresses, and was then used at the back of his ‘semi-fit’ lines in the mid-50s – dresses and jackets fitted at the front, but with loose voluminous backs. In 1957 he shocked the fashion world with the introduction of the ‘sack dress’, a straight up and down shift dress, which completely eliminated the waist. At a time when Christian Dior’s hourglass shaped New Look was still dominant, the ‘sack’ was initially met with hostility from both clients and press. “It’s hard to be sexy in a sack!” cried the Daily Mirror. Like many of Balenciaga’s most radical designs, this look eventually filtered into the mainstream. The sack dress was the forerunner of the ubiquitous mini-dress of the 1960s – and remains a fashion staple today.

The baby doll dress, also from the late 1950s, continued the theme of abstracting the body, with its trapeze-like shape skimming the waist. This abstraction reached a pinnacle in Balenciaga’s designs of the late 60s, as can be seen in the dramatic four-pointed ‘envelope dress’ shown the year before he closed the house. A sculptural form, moulded from his favourite fabric – stiff but lightweight silk gazar. Although a big hit with the fashion press, only two were sold and one was returned because the client couldn’t figure out how to go to the bathroom in it.

Balenciaga dressed some of the most glamorous women of the 1950s and 60s. Mona Harrison-Williams, later Countess von Bismarck, was voted ‘best-dressed woman in the world’ the first time the accolade was awarded in the 1930s. Described by Cecil Beaton as a ‘rock-crystal goddess’, she dressed exclusively at Balenciaga, right down to her gardening shorts. Then there were the Duchess of Windsor, Grace Kelly, Jackie Kennedy (the president balked at the bills), Helena Rubinstein, Mrs William Randolph Hearst, and to this small sample of society clients could be added Hollywood stars such as Ava Gardner, Ingrid Bergman, Marlene Dietrich and Lauren Bacall.

Balenciaga liked to dress women who had a strong sense of style and his clients were often extremely loyal. When his fashion house closed in 1968 the news shocked his clientele who experienced a real sense of loss – Mona von Bismarck shut herself in her room for three days straight.

Unlike some other high-profile designers of the era, Balenciaga was a very private individual. He refused to court the press, but despite his elusive nature, for many a Balenciaga show was the closest fashion gets to a religious experience. Balenciaga did not appear at the openings of his collections. Nor did clients see him for fittings as a rule. He watched the shows from the doorway to the ateliers, peeking through a small hole in the curtains. By staying backstage he could concentrate on what he loved – the work.

Balenciaga led a revolution in fashion, and has consistently been revered by his contemporaries, including the likes of Christian Dior and Coco Chanel, and fashion leaders of today. French designer Emanuel Ungaro, who trained with Balenciaga, said it was he who: “laid the foundations of modernity” in fashion, and both Ungaro and Andre Courrèges, another Balenciaga protégé, took forward their teacher’s minimalist aesthetic into the space-age chic of the 1960s.

The closure of Balenciaga’s fashion house in 1968, and his death four years later, marked the end of an era. Yet the master’s innovative pattern cutting, use of new materials and bold architectural shapes have remained influential. In 1986 the Balenciaga label re-launched under a series of creative directors. Of particular note are Nicolas Ghesquière – widely credited for reviving the label from 1997 to 2012 – and Demna Gvasalia, the current creative director who ensures the name Balenciaga is on everybody’s lips today. Both designers have worked closely with the Balenciaga House archives, looking to the original designs by The Master for inspiration in cut, shape and materials. As Gvasalia said of his latest collection, which drew heavily on iconic pieces by the house-founder: “It is important to know the past in order to build the future.”

In the 1950s, the later phase of his career, Balenciaga pioneered new shapes never before seen in women’s fashion. These radical designs evolved gradually as he refined and reworked the same ideas from season to season. Volume filled the ‘balloon hems’ of his early 1950s’ dresses, and was then used at the back of his ‘semi-fit’ lines in the mid-50s – dresses and jackets fitted at the front, but with loose voluminous backs. In 1957 he shocked the fashion world with the introduction of the ‘sack dress’, a straight up and down shift dress, which completely eliminated the waist. At a time when Christian Dior’s hourglass shaped New Look was still dominant, the ‘sack’ was initially met with hostility from both clients and press. “It’s hard to be sexy in a sack!” cried the Daily Mirror. Like many of Balenciaga’s most radical designs, this look eventually filtered into the mainstream. The sack dress was the forerunner of the ubiquitous mini-dress of the 1960s – and remains a fashion staple today.

The baby doll dress, also from the late 1950s, continued the theme of abstracting the body, with its trapeze-like shape skimming the waist. This abstraction reached a pinnacle in Balenciaga’s designs of the late 60s, as can be seen in the dramatic four-pointed ‘envelope dress’ shown the year before he closed the house. A sculptural form, moulded from his favourite fabric – stiff but lightweight silk gazar. Although a big hit with the fashion press, only two were sold and one was returned because the client couldn’t figure out how to go to the bathroom in it.

Balenciaga dressed some of the most glamorous women of the 1950s and 60s. Mona Harrison-Williams, later Countess von Bismarck, was voted ‘best-dressed woman in the world’ the first time the accolade was awarded in the 1930s. Described by Cecil Beaton as a ‘rock-crystal goddess’, she dressed exclusively at Balenciaga, right down to her gardening shorts. Then there were the Duchess of Windsor, Grace Kelly, Jackie Kennedy (the president balked at the bills), Helena Rubinstein, Mrs William Randolph Hearst, and to this small sample of society clients could be added Hollywood stars such as Ava Gardner, Ingrid Bergman, Marlene Dietrich and Lauren Bacall.

Balenciaga liked to dress women who had a strong sense of style and his clients were often extremely loyal. When his fashion house closed in 1968 the news shocked his clientele who experienced a real sense of loss – Mona von Bismarck shut herself in her room for three days straight.

Unlike some other high-profile designers of the era, Balenciaga was a very private individual. He refused to court the press, but despite his elusive nature, for many a Balenciaga show was the closest fashion gets to a religious experience. Balenciaga did not appear at the openings of his collections. Nor did clients see him for fittings as a rule. He watched the shows from the doorway to the ateliers, peeking through a small hole in the curtains. By staying backstage he could concentrate on what he loved – the work.

Balenciaga led a revolution in fashion, and has consistently been revered by his contemporaries, including the likes of Christian Dior and Coco Chanel, and fashion leaders of today. French designer Emanuel Ungaro, who trained with Balenciaga, said it was he who: “laid the foundations of modernity” in fashion, and both Ungaro and Andre Courrèges, another Balenciaga protégé, took forward their teacher’s minimalist aesthetic into the space-age chic of the 1960s.

The closure of Balenciaga’s fashion house in 1968, and his death four years later, marked the end of an era. Yet the master’s innovative pattern cutting, use of new materials and bold architectural shapes have remained influential. In 1986 the Balenciaga label re-launched under a series of creative directors. Of particular note are Nicolas Ghesquière – widely credited for reviving the label from 1997 to 2012 – and Demna Gvasalia, the current creative director who ensures the name Balenciaga is on everybody’s lips today. Both designers have worked closely with the Balenciaga House archives, looking to the original designs by The Master for inspiration in cut, shape and materials. As Gvasalia said of his latest collection, which drew heavily on iconic pieces by the house-founder: “It is important to know the past in order to build the future.”

essence info

Balenciaga: Shaping Fashion, sponsored by American Express, at the V&A MuseumExhibition runs until Sunday 18 February 2018

Daily: 10am to 5.30pm. Friday: 10am to 9.30pm

Tickets: £12. Concessions apply. Advanced booking recommended

Website: www.vam.ac.uk

“Haute couture is like an orchestra whose conductor is Balenciaga. We other couturiers are the musicians and we follow the direction he gives.”

Christian Dior